Russia’s Reliance on Imports Has Dramatically Decreased as Its Diversified Economy Has Substituted Most Imports

Russia’s Reliance on Imports Has Dramatically Decreased as Its Diversified Economy Has Substituted Most Imports

8,484 viewsThe Russian Central Bank is guided (among other considerations) in its inflation expectations by statistics produced by Rosstat (Russia’s governmental statistics agency) concerning the size of Russia’s imports relative to domestic production. The bank’s inflation expectation in turn is – judging by their policy statements – the decisive factor in its interest rate policy. Unfortunately, it seems that Rosstat has in its published statistics grossly overestimated the share of imports. According to the agency, the share of all imported products of the “consumer basket” would be 38%. Our research shows that the true figure cannot be more than 24%. When approaching the question from different angles we have derived results in the range of 4.9% to 24%.

The biggest problem in Russia’s economy is not its relative dependence on oil and gas revenue, rather it is the punitively high borrowing costs that should occupy the top spot in policy concerns. The Central Bank has been keeping its key steering rate at an inordinately high level of 11% although inflation has long ago fallen well below that. By end of March, the inflation for the past 12 months was down to 7.3% and running forward at a rate of approximately 6%. – Here, I must digress a bit to alert to a stupefying logical flaw in the thinking of as well central bankers and economic analysts. When they speak about the inflation rate is, they refer to the accumulated inflation for the past rolling 12 months. But, that tells only what the inflation has been, not what it is and not what it will be in the future. Then they talk about matching interest rates to that inflation figure, but obviously the interest rates they set apply for the future and not the past. There is then a glaring mismatch right there at the root of their reasoning as the inflation was looking back and interest rates going forward. It is as if the Central Bank would be steering a car by peering through the rear-view mirror. More adequately, they should therefore focus on the inflation expectations (running inflation) instead of the nice-to-know historical inflation. Hereby, the inflation of only the past few months should be taken into consideration to understand the dynamics. – The Russian Central Bank thus proceeds from quite erroneous premises in motivating its cutthroat interest policy by historical inflation records and “inflation risks” based on faulty statistics connected with a distorted view of the share of imports in the national economy. There is yet a third, perhaps more fundamental error, which is the neoliberal belief that inflation is strictly a monetary phenomenon. This when in fact the root cause of Russia’s inflation over the last two decades has been insufficient supply to meet the demand. Therefore, the immediate concern of the Central Bank should be to make affordable lending available for Russian producers. This should be done even at the risk of increasing the inflation in the short-term, because before the supply side is addressed it will not be possible to break the vicious cycle.

This article will provide some background to our criticism of the Central Banks failed policies.

The Impetus for the research

The economic analysts promoted by the liberal press seem to share a gloomy picture about Russia’s economic prospects. But, this is nothing new, they have done so for the past 15 years, having totally missed out on the fact that the Russian economy in the meanwhile grew tenfold. It is then only natural that they also are in the business of peddling the misconceptions as to the share of imports in the economy. One of them, Natalia Orlova, head of Alfa-Bank’s economic analysis, recently came out with a widely distributed op-ed, which also appeared in The Moscow Times. The thrust of the article was to show a purported total failure of Russia’s import substitution program which President Putin and his government has embarked on in order to lessen Russia’s dependency of the Western countries, which are waging a trade war against it. Baffled by her reasoning and the glaring deficiencies in the data Orlova refers to, I decided to get to the bottom of this issue myself.

Agriculture and food processing have made great strides towards total self-sufficiency

Ms. Orlova had backed up her claim about the supposed failure of import substitution by a series of macroeconomic statistics. She claimed that the agricultural sector grew by “only” 3.1%. Orlova did not think about digging a bit deeper to put the “only” 3.1% in perspective by pointing out that the overall GDP contracted by 3.7%, so, in fact the agriculture sector grew with as much as 6.8 percentage points more than the overall GDP. She added rather gleefully that the share of the agriculture in the GDP “barely budged” rising “slightly” to 3.5%. Yet, Orlova is here not comparing like with like when she on one hand refers to imports of food and on the other hand the agriculture sector of Russia. The correct comparison would be to compare imports with the total food production chain in Russia, which includes agriculture, fishing, and also the food processing industry. In fact, food processing also grew by 2% and contributed some 2% to the GDP, while the share of agriculture with fishing was to 4.2% (and not 3.5% as Orlova would have it). The combined figure then was 11.4% of GDP, a far cry from Orlova’s “only” 3.5%. – Could it be that she actually thought that the whole food sector was recorded under the agriculture headline?

The value of imports was $26.5 billion whereas the output of the domestic food production was $265.8. The share of imports was then roughly 10% of the domestic production. The idea here is that the total retail market consists of all food that is produced in Russia plus what has been imported minus what is exported. In reality a part of the imports are reprocessed in the domestic food industry whereas a part goes directly to retail. We do not have the break-up figure, therefore we calculated the 10% share of imports without inclusion of any of the imports in the value of the domestic production). If we detract the $16.2 billion which Russia exported, this would yield a 10.6% share of imported goods among the retail offering.

Ms. Orlova seems to be telling that the growth in agriculture, and food processing – which she ignored in her deliberations – is miniscule in comparison with the significant drop in imports by a total of 40% (actually it was 38.5%). It is as if she was reasoning that if one goes down by 40% the other must go up as much. She is here a hostage of her own faulty premises, thinking that the imports play such a significant role in the total that the percentage growth in domestic production should equal the percentage drop in imports. The problem here is that the share of imports was so inferior to the domestic production to start with that even a huge drop in the former did not show through as a dramatic percentage rise in the latter. In fact, the domestic production grew by $26.4.billion PPP-adjusted dollars in 2015, that was twice the $13.2 billion drop in imports. Thus, the domestic industry did not only make up for the decline in imports but grew additionally with as much.

This then should address Ms. Orlova’s bewilderment as to why the domestic production shows a smaller percentage growth than the corresponding drop in imports.

Why PPP-adjusted figures

Why do we want to make the comparison in PPP, that is, purchasing power parity? The answer is simple: because we are comparing the share of imports with local production. The PPP adjusted accounts represent by definition volumes of goods produced whereas the nominal figure reflects merely speculative fluctuations in currency rates. The PPP-figures are not without fault, but they are for sure much more accurate than the nominal once in this respect.

The grossly wrong presupposition that imports would represent 38% of a consumer basket

Let’s now look at another of Ms. Orlova’s controversial claims, which goes in the same vein as the ones we already discussed. Orlova refers to data she has picked up at a recent Central Bank briefing. According to that information, the share of imports in the “consumer purchases” had “barely” decreased from levels of 43-44% in 2012-2013 to 38% in 2015. Although that represents a decline by one tenth, it led her to conclude: “This is actually bad news: It means that even the halving in the value of the ruble has failed to cause a structural shift in the real sector”.

We have already addressed the wrong assumptions inherent in Ms. Orlova’s reasoning, but we must take a closer look at this “consumer purchases” argument. The problem stems from something that Rosstat records as “share of imports in the consumer basket”. The consumer basket aims at capturing the total volume of retails sales and all end consumer uses independent of form of trade. The statistics on this share of imports in the consumer basket is supposed to be done on a volume basis (Rosstat internal instructions, November 29, 2013, No. 457), however, arriving at the figure 38% as the share of imports can under no conditions be in reality based on volume, as should be evident from the data we present in this report. It seems that the questionable figure has been arrived through using the nominal rate of the U.S. dollar and other faulty premises.

The consumer basket of Rosstat is divided into two components: 1. Food, and 2. Non-food (consumer goods). In one data file, Rosstat informed that for 2015 the share of imports in non-food retail sales was 39% (44% in 2013); correspondingly the food imports were 30% in 2015 (36% in 2013). In another connection, Rosstat gave the total of food and non-food imports as 38%. This is peculiar because according to yet other data the share of non-food sales in total retail was 51% and food sales was 49%. The weighted average of the non-food (39%) and food (30%) should then be 34.6% and not 38%. This would actually mean a considerable decline by almost a quarter from the pre-sanctions 44-43% even within this – admittedly dubious – set of data. However, even this data must be wrong as it has been shown above, and as we shall proceed to show by reference to yet more data.

We do not know by which way of reasoning Rosstat has arrived at the above-cited ratios, however, more straightforward methods are available to refute them as we have already seen. Another obvious method is to compare the data on the dollar values of imports and the retail market respectively. We do not possess enough details to perform the analysis on the non-food part, therefore we will restrict our analysis to the food sector, which should be quite sufficient to prove the point.

In 2015, Russian retail sales amounted to 27.5 trillion rubles, or $454 billion. The share of food in this was 12.4 trillion rubles, or $204 billion. Food imports in turn amounted to $26.5 billion. The problem we face in working this data is that the amount on imports represents wholesale and thus comes net of the retail mark-up. For comparison, we must therefore assume a mark-up, which must for comparison be added to the import prices. We have decided to resort to a generous estimation of a 75% mark-up. In this case, we would have imports worth $46.4 bn in the retail chain versus a total retail sales value of $204 bn. This calculation yields a share of imported food in retail sales of 22.7%. (Assuming a 100% mark-up the figure would be 26%).

Russia’s imports in a global comparison

When one debates Russia’s dependency on imports, it is in fact unnatural and wrongheaded to restrict the arguments to the invented figure of share of imports in the consumer basket, for at the end of the day all imports (net of exports) end up in the consumer basket one way or another. That is inherent in the very definition of GDP, which is based on the concept of value-added through the various stages of production. That is why the most straightforward comparison would be by way of relating all imports to the size of the domestic economy.

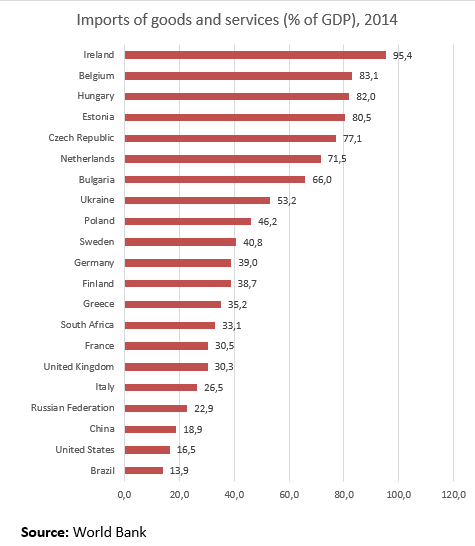

In 2015, the value of imported goods amounted to only 4.9% of the total PPP-adjusted GDP, even of the nominal GDP their value was only 13.8%. In a global context the importation of services is usually added into the comparison. This would yield for Russia a share of 7.3% of imported goods and services in the GDP (20.4% of the nominal GDP). Chart 1. Provides comparative data for selected countries. The problem with the chart, however, is that it is expressed in nominal GDP, which seriously distorts the data as it does not capture the real volumes of the economy the way the GDP expressed in PPP does. However, already in this chart with nominal GDP data for 2014, Russia’s share of imports was in the lower end of the countries. When we consider the fresh data from 2015 and the more relevant PPP-adjusted figure of 7.3%, then we will recognize that Russia indeed is exceptionally little dependent on imports.

CHART 1

Enormous Russia imports only twice as much as tiny Finland

We are reminded that this whole issue stems from the Central Bank’s misguided concern that imports make up too big a proportion of the goods sold on the Russian market, which has led them to overblow their expectations on inflation risk. They reason that a devaluation of the ruble would push up prices of imported products and because of their supposed huge share of the total would then cause an overall increase in prices. Therefore, it is good to consider yet something more, namely the fact that more than 10% (and growing) of imported foods stem from Belarus and other C.I.S. countries, which are either directly priced in rubles (most notably Belarus) or indirectly through the effect that the currencies of the countries follow the ruble dynamics.

That Russia’s imports presently are indeed very low is evident from a comparison with those of Finland, its tiny neighbor. In January 2016, Russia’s imports were down to $9.1 billion, which is only approximately twice the size of what Finland imported in the same month even though Russia has a 30 times bigger population.

The cost of Russia’s food imports equals only 15 USD per person, per month

The present level of imports is actually very low for a country the size of Russia. The total food import value of $26.5 divided by the number of Russia’s population (146.5 million) yields an annual cost of $181 per capita; the monthly equivalent would then be $15 and the daily 50 cents. Thus, each Russian resident would contribute on average 15 dollars per month to pay for the imports. Through the mark-up effect (of 100%) this would signify that each one pays in retail 30 dollars per month for imported foods. This can be put into perspective by comparing it with the total per capita expenditure on food. According to Rosstat, that was $126 (7,600 rubles) per month. By these considerations, the share of the value of the imported food would thus be 24%.

We may further relate these figures to the total disposable income of Russians, which was 30.5 thousand rubles per capita (3rd quarter 2015). Russians would then on average spend a quarter of their income on food, and only 6% would be spent on imported food (through the mark-up effect).

Here is a link to an article where we have argued that the Russian economy is far more diversified than it is generally maintained.

Would you like to share your thoughts?

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

3 Comments